Three Cameras

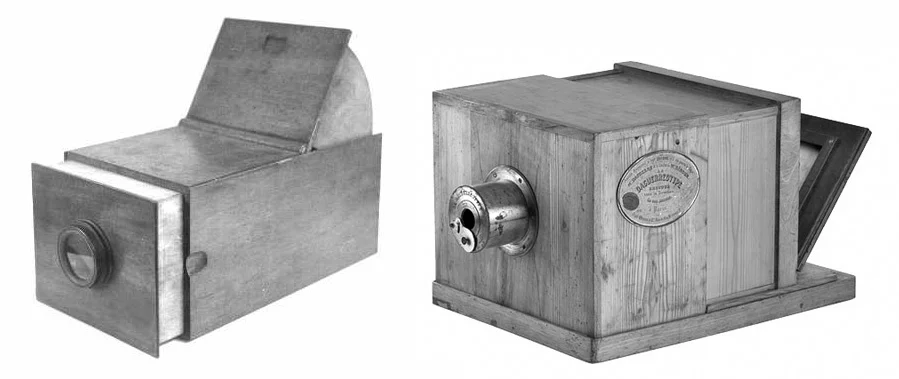

The photographic camera owes much of its design to the camera obscura—a dark box with a lens to focus an image on film/paper/digital sensor. Put an early 19th century camera obscura and an original Daguerreotype camera side by side, and you would be forgiven for not being able to tell the difference:

Left, Camera Obscura, c.1800. Right, Daguerreotype Camera, 1839.

Photography is primarily a chemical invention. The camera obscura’s optics and form factor were repurposed into a new device. The photographic camera took a “drawing aid” and made capturing images from life “drawing-less.”

Poor camera lucida. The promise of direct images from life permanently fixed to paper made all other drawing aids obsolete. Who would draw if they could just snap a pic? To add insult to the obsolescence, the camera obscura-inspired design of the photographic camera gives everyone the impression that the obscura—not the lucida—was the superior drawing tool. And we who use the lucida know that’s just not true.

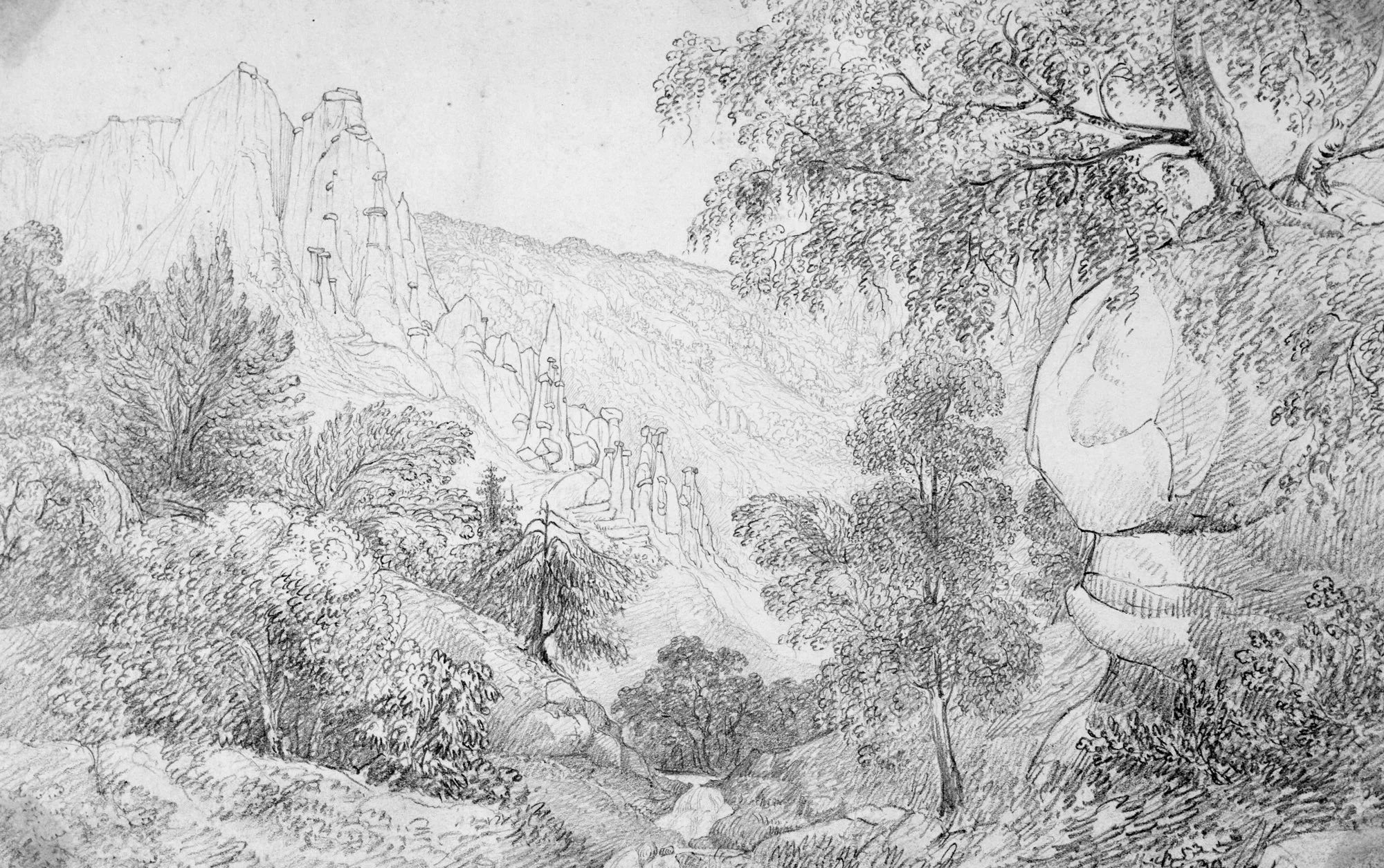

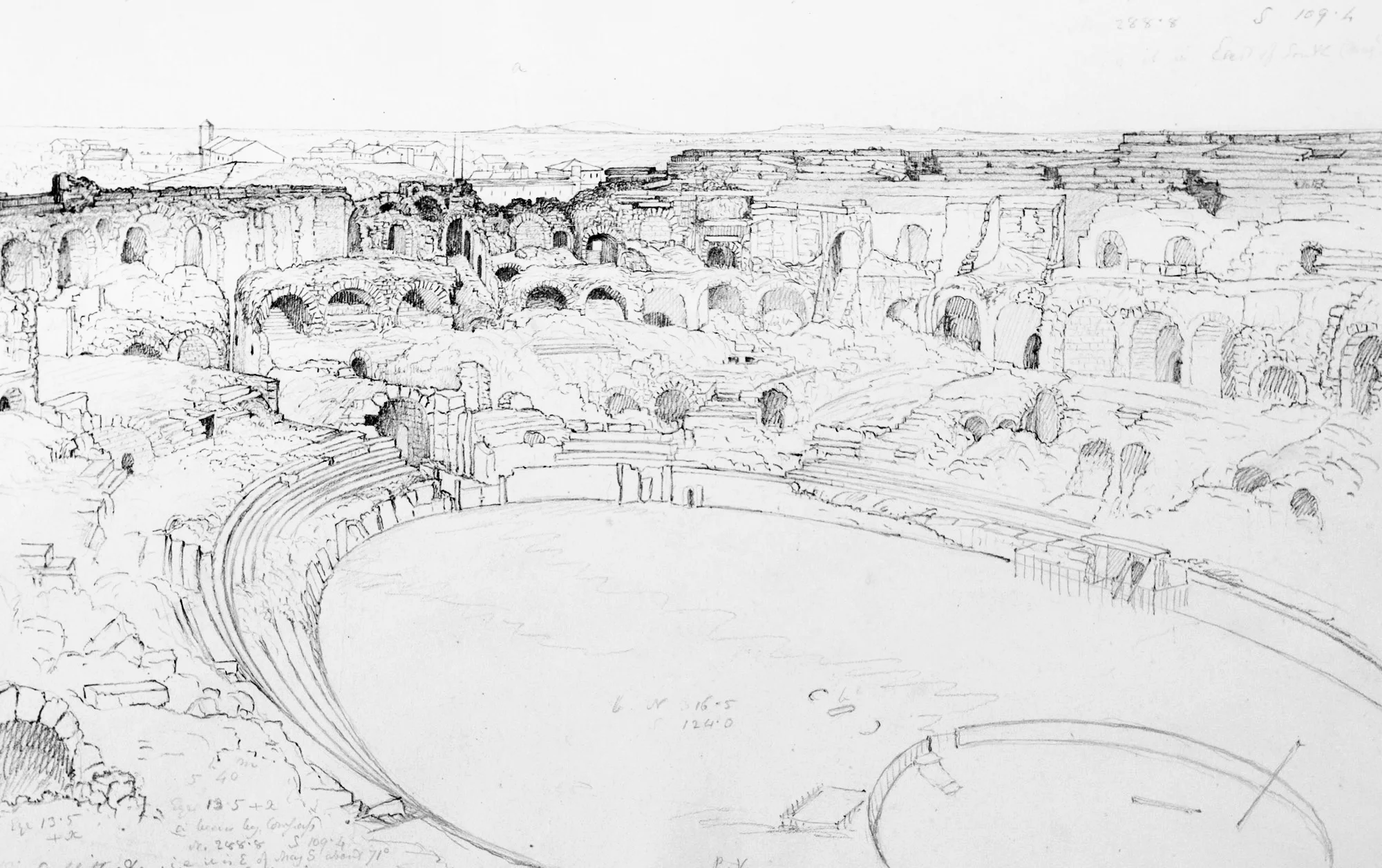

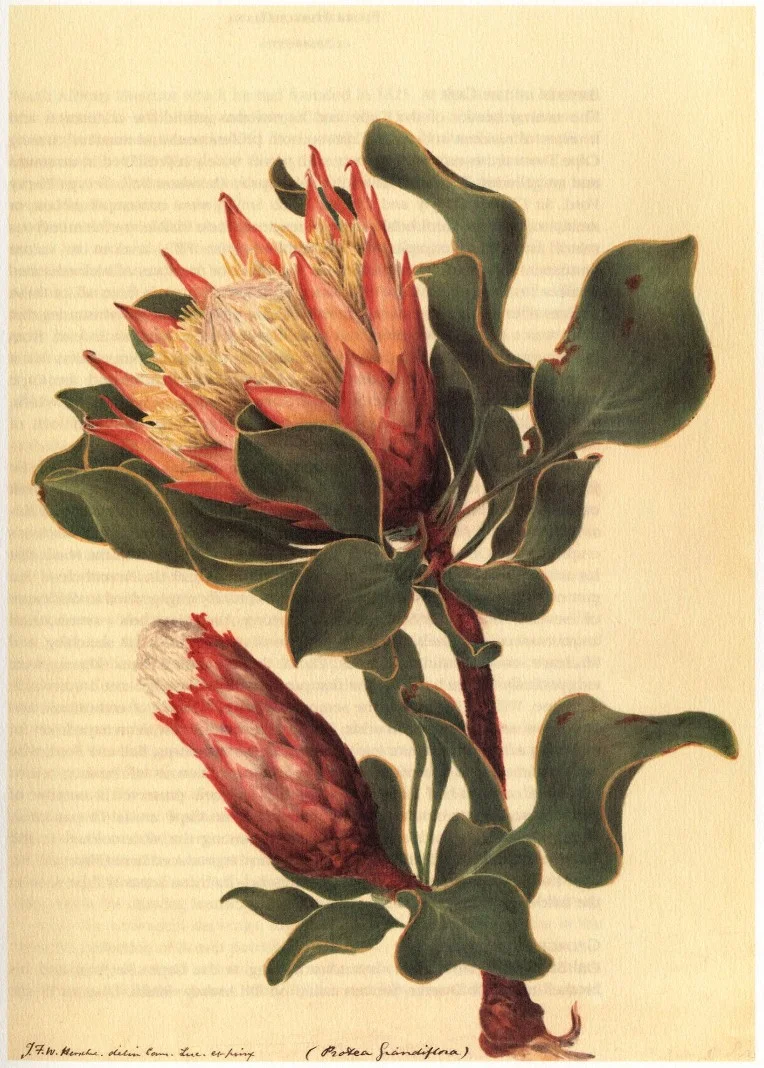

But the lucida plays a much more important role in the development of photography than the simple hole-in-a-box of the obscura. One of the great users of the Camera Lucida was Sir John Herschel (1792-1871), who—in addition to being a famous astronomer and chemist—used the drawing device in his youth as he studied botany specimens, scenes of import to the Empire (such as the new observatories he built in South Africa), and landscapes while on holiday. His collection of drawings comprise one of the most accomplished camera lucida portfolios known.

Sir John Herschel, Clay Columns at Stalde-in-the-Visp Thal Valais Sept. 4 1821

Sir John Herschel, Interior of the Amphitheater Nimes, Sept. 21, 1850

Sir John Herschel, Protea Cyanaroides, 1835

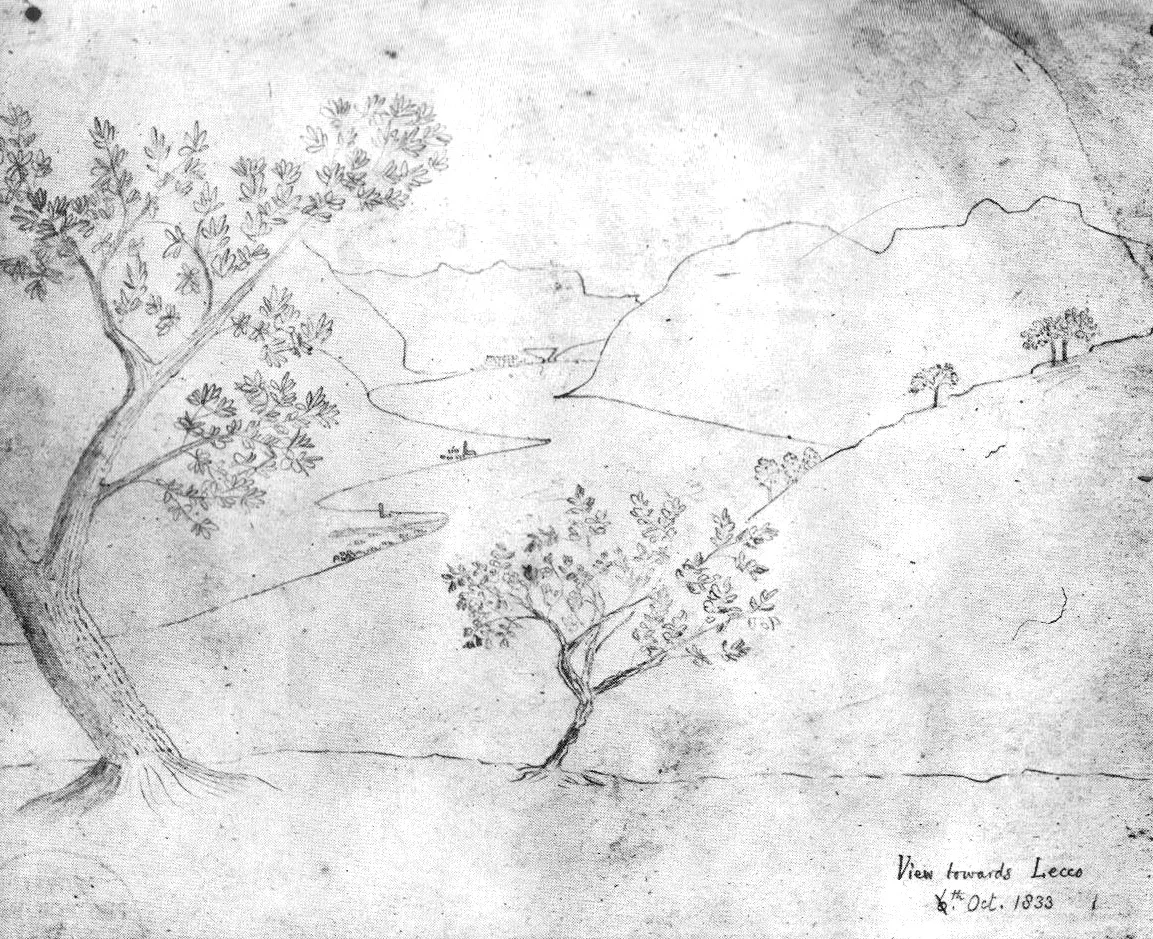

Herschel would encourage his friends to use the camera lucida when on holiday together. Close friend William Henry Fox Talbot (1800-1877) tried to draw with his camera lucida while on his honeymoon with his new wife in Switzerland and Italy. He commented in his memoirs how frustrated he was with the process, and that he was not satisfied with the outcome. He remarked in 1833: “when the eye was removed from the prism—in which all looked beautiful—I found that the faithless pencil had only left traces on the paper melancholy to behold.”

Henry Fox Talbot, View towards Lecca, drawn with a camera lucida, 1833

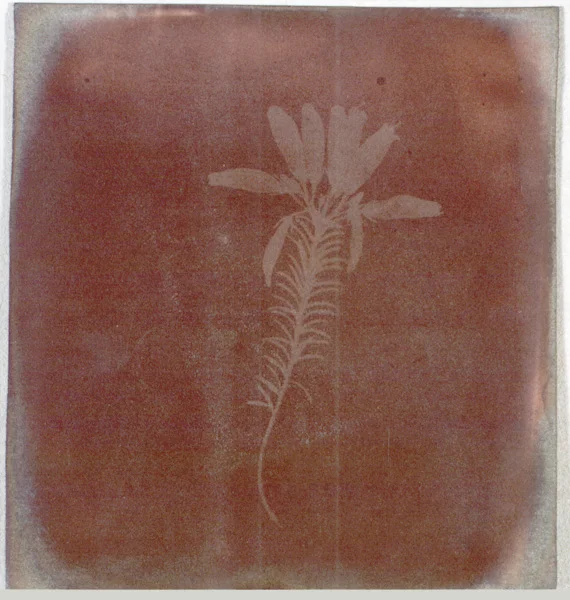

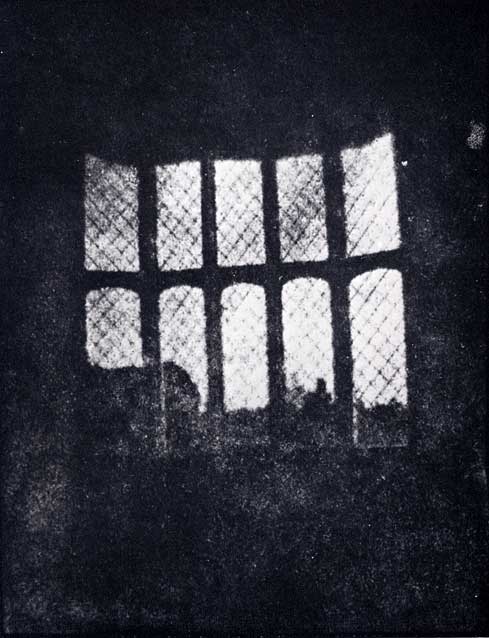

Talbot set out to do something about this unfaithful method of rendering. With Herschel’s help, he spent the next several years trying to chemically fix images to paper—the process we now call photography. He succeeded in 1835, making direct image prints of objects (what we would today call photograms) and lensed images of his surroundings at Lacock Abbey.

Henry Fox Talbot, “Photogenic Drawing” of Erica Mutabilis, 1839

Henry Fox Talbot, Lacock Abbey, 1835

Talbot was inventing a whole new medium, but since he was still in a pre-photographic mindset, he called his images “photogenic drawings.” (Herschel would coin the term “photography” in 1839.) When, in 1839, Louis Daguerre announced his photographic process to the world, Talbot unveiled his years of work. He subsequently published large volumes of his early images, starting in 1844 using his newly developed method of commercial photographic printing (an evolution of his calotype process).

It was Talbot’s frustration with the camera lucida that directly led to the invention of photography as we know it. And in a nod to those inspiring difficulties, Talbot calls his first book of photographs The Pencil of Nature.