The Camera Lucida: A History

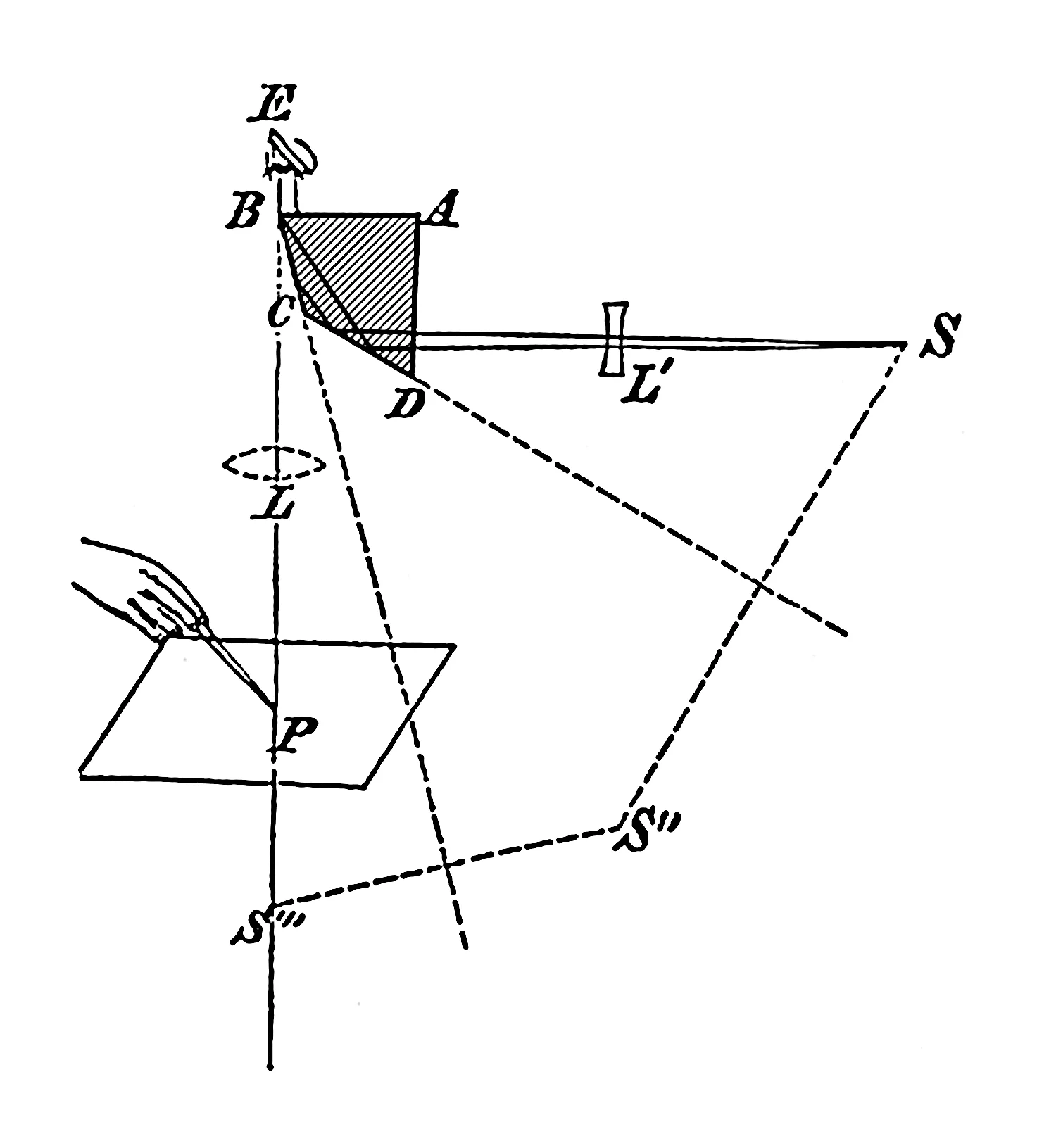

In 1807, Sir William Hyde Wollaston patented the Camera Lucida—and brought life-drawing to a whole new level. Wollaston’s device was simple: a prism on an adjustable stand. When an artist looks down through the prism, they see the world in front of them, plus their hand on the page, combined in perfect superimposition.

Wollaston’s prism optics, 1807

In short, a camera lucida allows you to trace what you see. And it does so in full daylight; there’s no need for a dark shroud or enclosure, as with a camera obscura. And that is the magic of the camera lucida: it’s portable, easy to use, and—with a little practice—you just copy the world onto your page with a confident hand.

By the mid-1800s, camera lucidas were everywhere. Indeed, the device is so effective in assisting accurate life-drawing that, according to the controversial Hockney-Falco Thesis, it’s now believed that many of the most admired drawings of the 19th Century, such as the Neoclassical portraits of Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, could only have been made with a Camera Lucida. This becomes astonishingly clear if you try one—an experience we hope to share with as many people as possible.

The Camera Lucida was the latest in a quest for automated drawing stretching back to the Renaissance. Almost immediately after the invention of linear perspective—a set of graphic and mathematical rules for constructing realistic drawings—artists proposed mechanized ways to draw from life. Using screens, strings, and articulated mechanical linkages, these drawing machines promised ever-increasing ease for the aspiring sixteenth century artist. The Camera Obscura, specular surfaces like convex/concave mirrors, and advances in lens grinding made the seventeenth century the optical century. This lineage leads straight to the 1800s, when Wollaston creates the most advanced drawing aid yet—the Camera Lucida.

The Camera Lucida and Photography

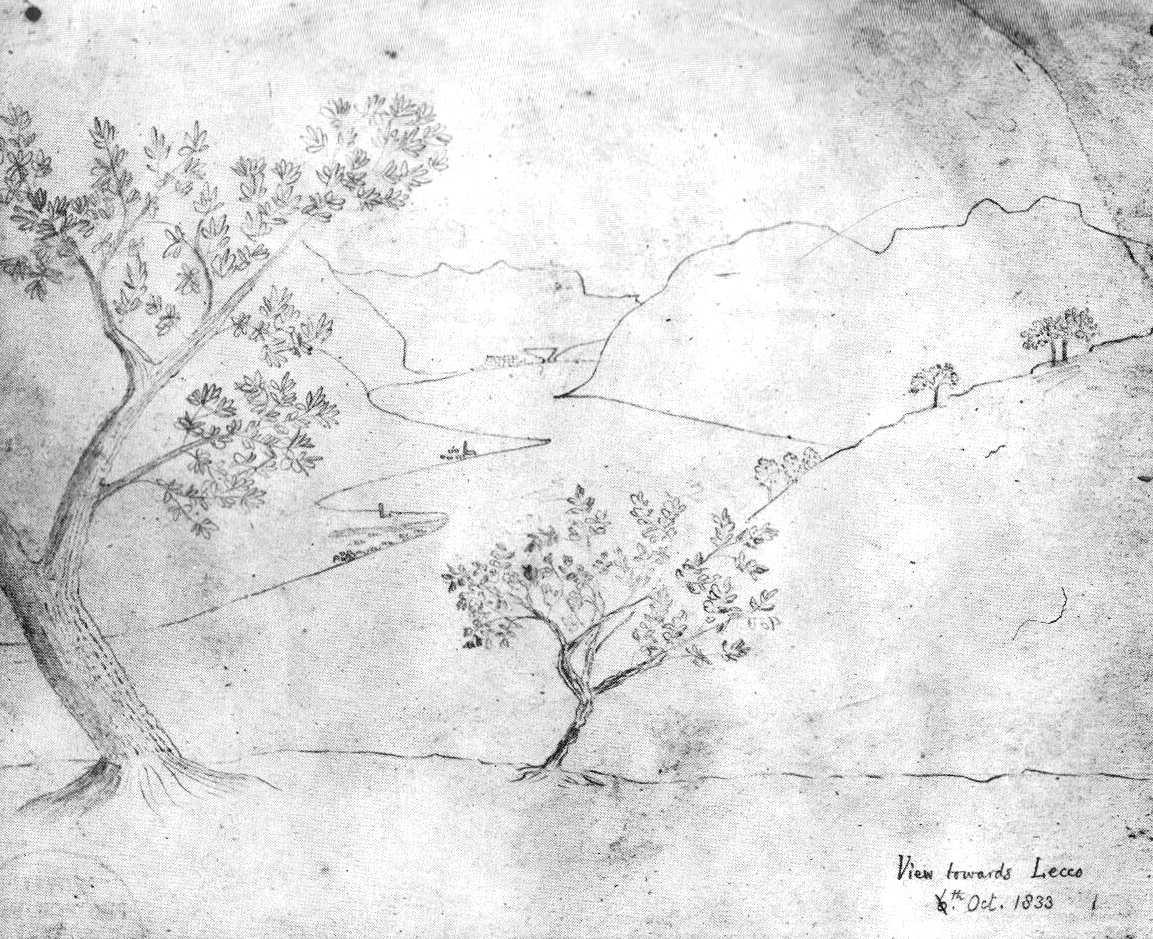

The Camera Lucida sits at a pivotal moment in imaging history. Famed English astronomer Sir John Herschel was an avid user of the Camera Lucida, and often drew with friends on holiday. Close friend William Henry Fox Talbot, not as talented a draughtsman, was disappointed in his experience. He remarked in 1833: “when the eye was removed from the prism—in which all looked beautiful—I found that the faithless pencil had only left traces on the paper melancholy to behold.”

William Henry Fox Talbot, View towards Lecca, made with camera lucida, 1833

Talbot set out to do something about this unfaithful method of rendering. He spent the next several years trying to chemically fix images to paper, the process we now call photography. He succeeded in 1835, making direct image prints of objects (what we would today call photograms) and lensed images of his surroundings at Lacock Abbey. In a nod to his use of the camera lucida and his frustration that spawned photography, he called his first photographic publication The Pencil of Nature.

Historical Examples of Camera Lucida Drawings

The Camera Lucida’s popularity and longevity—even as photography emerged—was due to its versatility. The instant image projected on your page means you can quickly draw a portrait without tiring your subject or landscapes, where changing light presents a challenge. It also works as a copying device, allowing the artist or engraver to duplicate images at various scales. Its ease also made drawing appealing to the amateur artist, inviting new audiences to take up the pleasure of drawing. Some examples:

Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres

Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres, The Alexandre Lethière Family, 1819

According to the Hockney-Falco Thesis, Ingres used a Camera Lucida to do his incredible pencil portraits. Part of the evidence is in the drawing itself. Note the quick yet confident strokes in the clothing. Tracing an image leads to loose yet precise lines, difficult to do solely by eye.

Christen Købke

Christen Købke, Portrait of Sophie Frimodt, 1836

Købke was one of the great figures in the Golden Age of Danish Painting, and a student of C.W. Eckersberg, “The Father of Danish Painting.” Eckersberg was an avid proponent of drawing aids, and it would seem that this ethic was passed down to his students in the form of the recently invented Camera Lucida.

Like Ingres, Købke’s pencil strokes are precise yet loose, particularly in the subject’s clothes and shoulders. This is a tell-tale marker of the camera lucida—tracing an image yields quick, confident strokes. A common misconception about the camera lucida is that it “automatically” gives the artist a realistic rendering. In practice, the optics provide a starting point. Begin with basic proportions, rough outlines, and overall composition. As the drawing progresses, the artist will use the camera lucida less, refining shade, tone, and texture unaided. Ingres and Købke could be revealing that process in their drawings—the “unfinished” areas were quickly sketched as preliminary pencil work. Refinement of the facial features provided the artist with the necessary detail to guide the transfer of the likeness to oil on canvas.

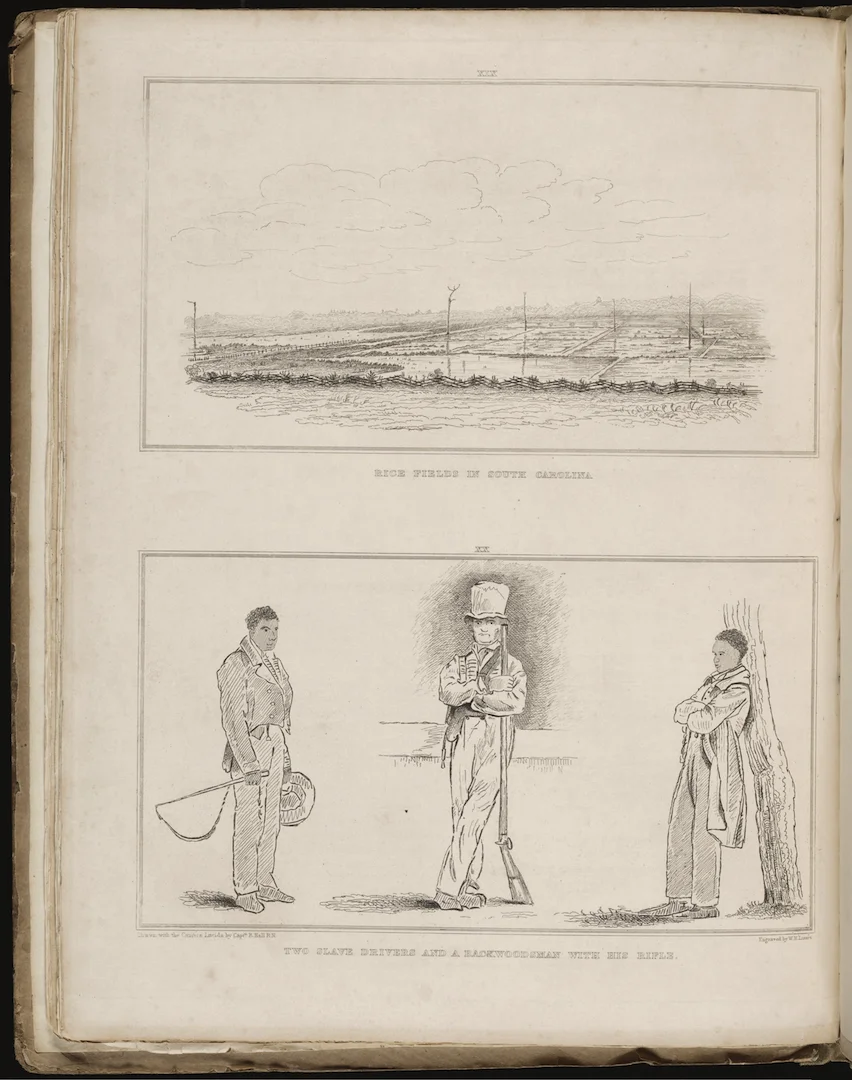

Captain Basil Hall

Capt. Basil Hall, Forty Etchings From Sketches Made With The Camera Lucida, 1827-28

British Naval Officer Basil Hall was—as experienced seamen were at the time—incredibly well traveled. Unlike most sailors, he kept journals throughout his career providing first hand accounts of distant explorations. After retiring from service, Hall traveled to North America with a Camera Lucida and published accounts of his journey. The Camera Lucida provided the amateur draughtsman with an accurate way to depict the landscape, culture, and dress of the young America before the invention of photography.

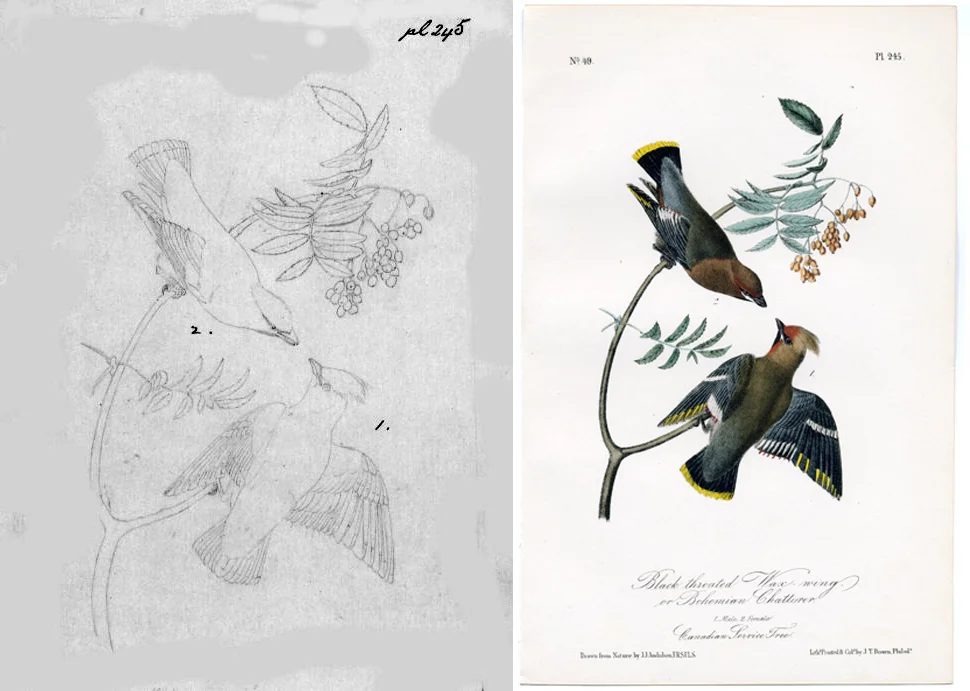

Audubon and the Royal Octavo Edition (1839)

John W. and John James Audubon, Birds of America Plate 245: Black-Throated Wax Wing, 1839. (Left: John W. Audubon’s original Camera Lucida Pencil drawing. Right: as printed in the Octavo Edition, Colored and printed by J.T.Bowen)

Perhaps the most famous example of a Camera Lucida used as a copying device is Audubon’s Royal Octavo Edition of “The Birds of America.” Originally produced as an enormous folio of hand-colored prints, Audubon’s son John W. spent several years using the Camera Lucida to reduce the large prints to octavo size (1/8th size) for a more affordable version of the avian catalog.

Frederick Catherwood

Frederick Catherwood, Lithograph of Stela D at the Mayan site of Copán. Original drawing made on site with a camera lucida. Published in “Views of Ancient Monuments in Central America”, 1844

In 1839, Catherwood traveled to Mesoamerica with writer John Lloyd Stephens after reading accounts of Mayan ruins published several years earlier. Catherwood was inspired by the verbal accounts of newly discovered archeological sites but, trained as an architect, sought more detailed visual evidence of the intricate carvings and structures. They published Incidents of Travel in Central America (1841) and Views of Ancient Monuments in Central America (1844) to great acclaim. Their travels, documented by Catherwood and his camera lucida and printed with fantastic detail, inspired new interest in Mayan culture and expeditions of Central America.

See more examples at the Victoria & Albert Museum, London.