Long-form essay written for Creative Applications Network and published on the occasion of the launch of HOLO, their new magazine. Original article posted here.

Pictus Interruptus and other Notes on the Selfie

1A. Technological Transparency

This is a self portrait from 2001. I shot it on 35mm Kodak Tri-X film with my analog SLR. I was quite satisfied with it at the time, as the photo seemed to capture much of what interested me in photography: images that were self-conscious about their own making; techniques that highlighted innate processes and properties. Ostensibly this is a photo of me, but the background is in focus. It’s a grainy print; the texture spoke to the material quality of analog photography. And the shadow of the camera and my arm holding it seemed to collapse space into a perfect staging of technological transparency. That is, the means of production are represented in this representation. Above it all, the method by which the system is made apparent is the setting sun—original giver of light, maker of shadows. All elements required for a photograph are indexed here: the photographer, the subject, the camera, light-sensitive celluloid, and light. This photograph, in essence, is about photography, and less about me. Or at least that’s how 26-year-old me thought of it. Thirty-nine-year-old me looks at this now and muses: “Kinda looks like a selfie.”

2A. The Currency of Selfies

If I can’t show it

If you can’t see me

What’s the point

Of doing anything?

So sings Annie Clark (a.k.a. St. Vincent) in her Laurie Anderson-esque, intellectual-yet-anxious pop anthem “Digital Witness” (2014).

2B.

Dutch artist Zilla van den Born told her friends she was going on a five-week tour of Asia. She posted photos on Facebook and Skyped home throughout her trip. It turns out she never left her home city of Amsterdam. Everything was constructed faked. Why? “I did this to show people that we filter and manipulate what we show on social media,” she told Dutch journalists. “We create an online world which reality can no longer meet.”

Looking through the photos shared with the public, one thing should have tipped them off: no selfies. The photos are almost naively ‘touristic’ in the 20th century sense: posing next to locals, or wide shots of her on the beach. As if she handed her camera to a stranger to take the photo. Who abdicates their role as documentarian anymore?

The lesson here: Don’t trust selfie-less vacation pics.

3A. Tourists

“In a little while we were speeding through the streets of Paris and delightfully recognizing certain names and places with which books had long ago made us familiar. It was like meeting an old friend when we read “Rue de Rivoli” on the street corner; we knew the genuine vast palace of the Louvre as well as we knew its picture; when we passed the Column of July we needed no one to tell us what it was or to remind us that on its site once stop the grim Bastille.”

Mark Twain wrote this in his seminal travel essay The Innocents Abroad or The New Pilgrim’s Progress. Nearly 150 years ago, he described something every tourist today knows: ‘seeing Paris’ is partially a contract between what you expect to see or have pre-viewed, and the satisfactory fulfillment of that sight. Imagine if Twain had Google StreetView.

2C.

‘Selfie’ was the Oxford English Dictionary 2013 Word of the Year. Deal with it.

2D.

In which I moderate a conversation using other people’s words on the value of the selfie.

First, the hand-wringers:

“The selfie is reprehensible because it’s two levels of narcissism. First of all, you’re on a social media site. This, by itself, is a narcissistic thing to do. But for the selfie sender, this isn’t enough. No, they have to take their egos and lack of self esteem to another level and post pictures of themselves on these sites.”

Strong opening from the haters. Is narcissism really the problem?

“It’s less about narcissism—narcissism is so lonely!—and it’s more about being your own digital avatar.” —Marina Galperina, journalist and co-curator of the National #Selfie Gallery.

Interesting point. But isn’t “being your own digital avatar” problematic? Isn’t that just as solipsistic?

“This is, of course, tosh. Human beings have been picturing themselves, trying to hone their self-images, and showing off to their mates for centuries. The growth of photography brought a boom in selfphotography.” —Ben MacIntyre, “Me, My Selfie and I”, London Times

So we’ve always looked at ourselves. Is this the nature of photography?

“To me, photography is the simultaneous recognition, in a fraction of a second, of the significance of an event as well as of a precise organization of forms which give that event its proper expression.” Henri Cartier-Bresson, The Decisive Moment

Well, that may be so, but it feels like the selfie is the opposite of this. Is the selfie about the decisive moment frozen in time? Is it a documentary instant?

“The selfie makes us accustomed to putting ourselves and those around us ‘on pause’ in order to document our lives.” —social scientist and author Sherry Turkle

Right. Sherry has a good point: the selfie is not photography in the 20th century sense of ‘capturing’ life from behind the lens. The selfie demands stagecraft. And since the photographer and subject are in the same shot, there is no room for other photographic narratives; they concentrate entirely on picture-making. The world stops for the selfie. The selfie is a picture which by definition interrupts life—a vita interruptus.

What about the social media aspect of the selfie? What role does the network play in the selfie?

“Selfies strongly suggest that the world we observe through social media is more interesting when people insert themselves into it”

Go on…

“Rather than dismissing the trend as a side effect of digital culture or a sad form of exhibitionism, maybe we’re better off seeing selfies for what they are at their best — a kind of visual diary, a way to mark our short existence and hold it up to others as proof that we were here.” —technology columnist Jenna Wortham

So the selfie is a way to stave off the fear of being forgotten?

“What… photographs by their sheer accumulation attempt to banish is the recollection of death, which is part and parcel of every memory image. In the illustrated magazines the world has become a photographable present, and the photographed present has been entirely eternalized. Seemingly ripped from the clutch of death, in reality it has succumbed to it.” —Siegfried Kracauer, Photography, 1927

Whoa. So if there was this sense in 1927 when there were way fewer photographs, what happens now? How many photographs are actually out there?

“Yahoo estimates that 880 billion photographs will be taken (in 2014), and a survey taken by Samsung in Britain found that 17% of men and 10% of women take selfies. All together, that means a lot of selfies will be taken (this) year.” —bgr.com (December 24th, 2013)

So selfies number in the billions. And growing. That’s a lot of people looking at people looking at themselves.

0. Ground Rules

What is a selfie? Or, rather, what makes a photo a selfie? It’s not merely a self-portrait, as selfie-ologists will tell you. Because if it was just a self-portrait, then we’ve been making selfies since Narcissus. No, there are rules. And while there are many species of selfies, there are only a few relevant phyla. Sanctioned selfies must be one of the following formulas:

The Mirror Selfie. You just finished working out and flex your abs into the gym mirror (Yes, I’m talking to you, Bieber). Or maybe you take a break from the party with your BFF and snap a shot in the bathroom, with or without duckfaces. Or you are trying that new shirt at Urban Outfitters and you post that dressing room pic to Facebook for a fashion consensus. This schema uses the mirror to help frame the scene. A marker of the Mirror Selfie is the inclusion of the camera (phone) in the shot. The mirror selfie is also a selfie of the camera—the iPhone is taking a pic of itself as much as you are taking a shot of yourself.

[Alt-pop band Echosmith lead singer Sydney Sierota. At 17 years old, a selfie machine.]

The Outstretched Arm Selfie. The Cape Times (Cape Town, South Africa) created an ad campaign to proclaim “You can’t get any closer to the news.” They altered historical photographs into selfies, like this Jackie Kennedy photo with her husband from 1962:

The framed photographic space is more intimate with the outstretched arm. Why? The original photo is a candid moment of a receptive subject, but carries a fragment of intrusion from an outside party. Someone had to stick their camera in Jackie’s personal space to get that shot. The selfiefication may seem more self-conscious, but it’s also more intimate. In the original photo, you are looking into the car. In the new version, you are in the car with the Kennedys. Speaking of JFK, who seems to be an afterthought in the selfie version of that photo:

The Pictus Interruptus Selfie (with apologies to Ray K. Metzker). Congratulations, you’ve made it to Paris. You’ve never been to Paris, so you head straight for the Eiffel Tower. There it is. Like a good tourist, you take out your camera—which is actually your phone—and you frame the shot. Ten years ago, you would likely have snapped your shot with your point-and-shoot and saved the digital file for printing on Snapfish. Now that shot heads straight for online sharing. Oh, and that pic of the Eiffel Tower you would have snapped in 2004? In 2014 you stick your grinning face into that shot, essentially photobombing your own tourist shot. To do this, you hold your phone at arm’s length, and shoot using your front-facing camera so you can frame both your face and the background subject at the same time. This selfie is ostensibly about the scene, but the subject really is “me at that thing.”

2E.

“I haven’t been asked for an autograph since the invention of the iPhone with a front-facing camera. The only memento ‘kids these days’ want is a selfie.” —24-year-old pop-star Taylor Swift, in her op-ed in the Wall Street Journal (July 7th, 2014)

3B.

The ‘Disaster Selfie’ is a thing.

Survive a plane crash? Visit Chernobyl? Witness a car accident? Maybe it’s not my first reaction to take a selfie, but apparently it is to some. And the web publicly flogs those who are “insensitive” and shoot funeral selfies. What is so disrespectful about this selfie? Is it the “Look at ME at this place that should be about other people!” attitude? Perhaps. I do question the photographer for employing standard selfie postures in front of serious and often grim settings. Don’t pose all sexy-hands-on-hips for the Auschwitz selfie. Don’t smile with the casket in the background, asshole.

But the disaster selfie—and its parent, the Pictus Interruptus selfie—was inevitable. Twain knew it in 1869. It feels like just about everything to be seen has been photographed, leaving little for us to see for ourselves.

I was in Portland recently, walking across the Willamette River near sunset. I looked at the downtown view and thought “That’s pretty. I wonder how many mostly identical photos to this exist on the internet and in hard drives around the world.” The only way to make it mine is to stick the only thing no one else has into the photo: my face. So I bomb my own photo, because it has to be different and uniquely mine. It proves I was there; I didn’t just grab one of the thousands of similar images from the web. And if it’s an event, like my big holiday trip, or “I am at the One Direction concert!”, or my plane just crashed, all the more I need to identify this as my personal experience, with me in the shot, and the event behind me.

Furthermore, my own memory needs that kind of personal marker. If you’ve ever been to the Eiffel Tower, I challenge you to remember the Eiffel Tower as it was when you saw it and NOT remember your photos of it. Or better yet, someone else’s photos of it. How can we know we are remembering our own experiences with the number of photos we see everyday? Maybe we feel the need to take selfies to help anchor our photographs in our own timeline and not risk cross-contaminating our memory with Instagram posts. Pictus Interruptus is a vaccine against the scourge of ubiquitous images.

1B.

We love peeking behind the scenes. Reality shows and “making of” specials hold our post-modern attention. Technology—and more specifically, technology’s deft hand at distribution—has provided more access than ever before. A celebrity’s bathroom? The newest CGI techniques? Inner thoughts by your next-door neighbor? We’ve got Instagram, DVD extras, and blogs for that.

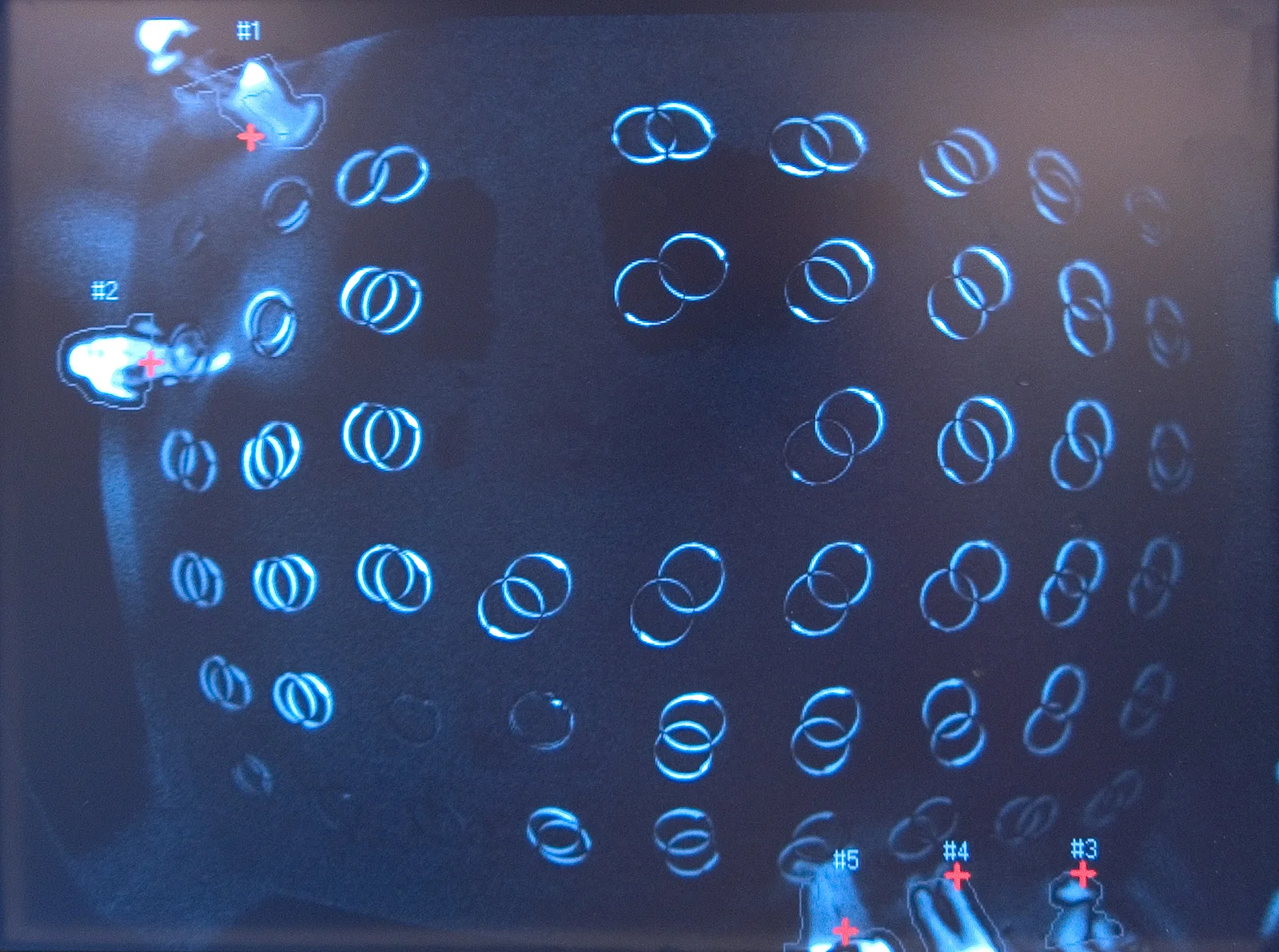

A debug view of Rafael Lozano-Hemmer’s Standards and Double Standards, Subsculpture 3 (2004).

In contemporary media art, debug screens have slipped into the final works. Like seeing the Matrix code trickle down, media artists are including the operational languages into works. Greg Borenstein, in his HOLO 1 article “Ghosts and Underwear”, credits several technological movements for this trend, namely open source ethics and a fascination with understanding the methods of cutting-edge tech. To wit: “The debug view demystifies technology by pulling away the curtain and teaching people how the magic is done.”

We want to see the recipe, because we want to learn for ourselves, and we want to be part of the action.

In related news, there’s a New Aesthetic you may have heard of. “Central to the New Aesthetic is a sense that we’re learning to ‘wave at machines’—and that perhaps in their glitchy, buzzy, algorithmic ways, they’re beginning to wave back in earnest”, says Matthew Battles.

Is the selfie New Aesthetic? Not really, but if the New Aesthetic is loosely about the ways the complex interactions between humans, technology and media make themselves visible, then the selfie is the largest, by volume, index of it.

1C.

James Bridle, as part of his essay for HOLO, took “surveillance selfies” by merely standing in the frame of London’s wide array of broadcast CCTVs. Wearing a bright pink shirt, Bridle is captured all around town. More importantly, he is looking at the camera in each image. Bridle converts surveillance into selfies by introducing a subject: himself. Surveillance doesn’t have a subject, it merely has a gaze. Subjects may appear later, if feeds are reviewed for criminal evidence, but surveillance cameras are just pointed in some direction. They don’t really look at anything.

Bridle presents photos of him looking at the camera taking a photo of him. When we look at these photos, the clandestine cameras cannot hide: we see the camera and its networked apparatus as much as we see a tiny figure in a pink shirt.

2E.

Design studio Onformative used facial recognition to find landscape-scale faces in Google satellite imagery because #earthselfie.

1D.

“People want to watch people having sex. That live component, the intimacy of it, adds an extra layer of feeling present. It creates the idea that it really is real, and I think people want that. They want to feel that this is really happening.” — Dr. Gail Saltz

We are so keenly aware of media production now. “Staged” pornography cannot hide the extra person in the room holding the camera. No matter the fiction portrayed, it can’t really be a surprising seduction because there’s a photographer in the room that is never acknowledged by the actors. The hidden production crew works for narrative cinema, but when you are seeking surrogates to physical intimacy, you want it as close to real as possible.

So thank you webcams and inexpensive camcorders. The amateur can make their own sex videos, and with it comes a mediated authenticity. Yes, this is video, and thus a framed construct between me and the performers, but the lighting is just from that lamp, and those are their sheets and that camera is just on their laptop on the dresser. Which means they are real people doing this for real, authentic and transparent. Actors having actual sex pales in comparison to real people having real sex.

2F.

When Ellen DeGeneres made selfie history with a live Oscars group selfie (technically it was a Bradley Cooper selfie, since he held the phone), people around the world Ate. It. Up.

Why not? Either this was peak selfie and a sign selfies would now start to die, or—to selfie lovers—it was a super-duper-mega celebrity selfie.

I couldn’t help but notice how average it was. Aside from the stage lighting in the theater (until very recently known as the “Kodak Theater.” Awkward.) and the dapper attire, this was like any other group selfie (a.k.a. the phonetically challenging ‘usie’).

Celebrities: they’re just like us! They gawk at their own visage instead of looking into the camera. Someone tries in vain to cram into the frame (Sorry, Jared Leto), and someone is caught behind someone else (Don’t worry, we know you’re there Angelina). They also use a camera phone with standard optics: a tiny lens susceptible to glare (just above Julia Roberts) and sensitive to subject movement (J-Law’s tilting head) or camera (er, phone) shake.

The selfie, now that it has reached the heights of celebrity, expresses its true power: it is democratized media. The rich and powerful don’t have better cameras or longer arms. They cant buy a better selfie, and they don’t seem to want to. Their selfie is an Android or iOS selfie, just like mine and just like yours. We all look the same in our selfie, and when we see the celebrity dressed down and subject to the same technical constraints we hold in our own pockets, we see something else. We see through other established media to something ‘authentic.’ This isn’t actor Bradley Cooper portraying someone in a movie. This also isn’t the real Bradley Cooper captured with a paparazzi telephoto lens. This is Bradley Cooper holding the phone, and we know that. The selfie—despite the contrived and self-conscious schema—is the most unmediated media today, because we are all concurrently selfie consumers and producers. We are aware of the outcome before we snap, and clued in to the production template of others’ selfies; we all stick to the agreed-upon conventions.

1E.

Painting, the pinnacle of representation for hundreds of years, moved away from mere documentation or verisimilitude once photography provided a superior technological result. (Yes, I’m oversimplifying the relationship between painting and photography in the 19th century, but let’s move on). Painting proposed new, conceptual goals like challenging the viewer to understand the nature of representation (Magritte), break down the physiological nature of sight (Impressionists) and open the mind to structures of the universe (Mondrian).

Meanwhile, Photography documented life in crisp details, eventually evolving into “decisive moments” (Cartier-Bresson) and “instant memories” (Kodak Marketing). Photography’s mandate was to “capture life as it is.” Photography is documentary, but photography rarely documents photography.

Art history records occasional self-investigatory pursuits in photography, like Harry Callahan’s formal experimentation through exposure, or conceptual photography from Kenneth Josephson. But while the public is all too familiar with painting’s radical departure from lifelike representation (“Pfft. My 2-year-old could do that”), the vast majority of amateur photographers are unaware and disinterested in the medium beyond ‘taking pictures of things’, with Instagram filters as their artful pursuits. What is photography? At the core, it’s a light-sensitive surface exposed to the world through a lens to focus the image. Chemistry evolved into pixels, but this fundamental arrangement has changed little since the mid-1800s.

Then someone put a camera on a phone. The camera became a feature—an afterthought—to an emerging technology, and proclamations of photography’s death soon followed. More people took photographs, but those were ‘just pictures.’ It would seem that the technological evolution leads to an artistic devolution.

Cameras began life as a large box with a large lens containing fragile plates doused in dangerous chemicals. Now? This is the state of photographic technology today:

- • Super lightweight to easily hold at arm’s length.

- • Framing is easy, since you have a bright screen with live view from forward-facing cameras. The tiny focal length and digital auto focus means no one wastes time focusing.

- • Digital photos are stored on memory cards, so images aplenty; no need for moderation when you have way more than 36 shots handy. Snap away! You probably have over 1000 photos on your phone right now.

- • It’s on a phone, which means people who didn’t really want a camera before have one because they need a phone.

- • Facebook is the largest photo archive in the world , so clearly people like sharing their pictures. That recipe makes selfies inevitable.

What selfies offer—their lasting legacy—is the transparency of technology and of the human-technology interaction. When we look at a selfie, we don’t see a person. We see a photo of a person taking a photo of themselves. Selfies are a worldwide, crowdsourced photography manifesto about what photography is: a photographer aiming an image-capturing device at a subject. And because each selfie includes all these parameters in the photo, via mirrors or outstretched arms, the selfie phenomenon is a giant self-portrait of photography itself.

1F.

So maybe my 2001 portrait wasn’t a selfie. I used a bulky technology that ONLY takes photos and it took practice to hold the camera just so. It was shot on analog film—black and white, no less—requiring me to finish the roll before I spent an hour developing it by hand. I then dried the negatives, made a contact print, selected a photo, enlarged it in a darkroom with filters and burning and dodging, passed the print through successive chemical baths, dried, flattened and matted the image. Slow, and very un-selfie.

But maybe it exists as a selfie because it wanted what selfies want. Maybe its transparency makes it a proto-selfie. Maybe the desire is enough.

I did scan the print and use it as my first Facebook avatar when I joined in 2006, but that was long before there were other selfies around. So maybe it is one now, indistinguishable from the billions of other indices of media transparency we post online. Because I look at this now and all I can see is a photo of me taking a photo of me. You know, a selfie.

* * * * *

![[Alt-pop band Echosmith lead singer Sydney Sierota. At 17 years old, a selfie machine.]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/58a8c1cdd2b8579b70b99827/1487539033115-RJRX52IATM1WQ9EKCY3I/image-asset.jpeg)