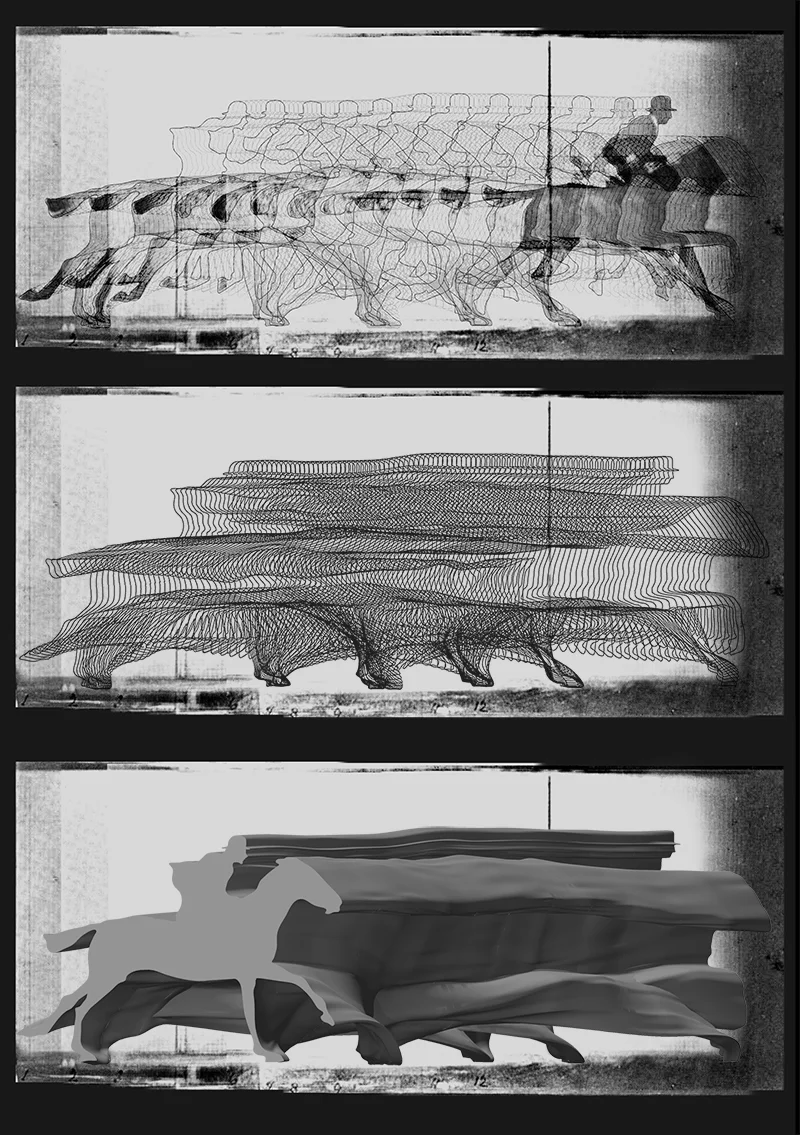

Profilograph (after Muybridge)

Eadweard Muybridge’s 19th century photographic studies of animal locomotion marked the beginning of cinema. What began as a way to settle a wager (does a galloping horse ever fully leave the ground?) evolved into a proof of concept: sequential photographs of action can be assembled to realistically present life in motion. Or, as we know it today: a movie. To capture the action, Muybridge used twelve still cameras at regular intervals to capture one cycle of a horse’s gallop. By cinema standards, this is quite sparse. There is a lot of data missing between each frame in comparison to the 30 frames per second of contemporary video.

Muybridge produced hundreds of studies of animals in motion. Plate 624—a running horse—is the basis for this project. Using a process I call Profilography—tracing and extruding a series of sequential contours or profiles—the twelve photographs become a continuous profile. Slicing through the extrusion yields new frames, derived from Muybridge but absent from his original sequence. Since the model is contiguous, there are an infinite number of frames that can be generated from the original twelve.

After 3D printing the digital model, each print is prepared for investment (lost-wax) casting. In traditional metal casting, a form must first be molded and cast in a series of steps to produce a wax version. That wax version is then slowly covered in a ceramic shell. The wax inside is burned away, leaving a void for the molten bronze. In this project, the 3D prints are directly cast in the ceramic shell and melt away when flash-burned. Since the parts can be made on demand by a 3D printer, this process obviates the need for intensive manual sculpting. The final piece is a 3D manifestation of 2D images originally made to represent 4D (temporal) action, exploring artistic methods across time: millennia of bronze casting, the 19th century (early cinema and photography), and the 21st century (computers and 3D printing).

Eadweard Muybridge, Animal Locomotion, Plate 624 (1887)