Pablo Garcia and Or Ettlinger are both explorers in the vast territories of virtuality – but they had never previously met. Both come from an architectural background, and both share an interest in the classical arts and a fascination with science fiction, as well as with the possibilities of digital technology. They are both academics, one teaching in Chicago, the other in Ljubljana. Yet their respective paths, views and activities are also quite different. On the occasion of Pablo Garcia’s exhibition and lecture in Aksioma in April 2014, we decided to arrange a meeting between them…

Or Ettinger: The first thing that struck me in your talk was when you clearly separated virtual from digital. It is one of the key points of my own theoretical work, but it was very refreshing to hear it from somebody else. What was your process of coming to that realization?

Pablo Garcia: Some of it is autobiographical. I was a teenager in the late 80s when we were seeing virtual reality as a popular phenomenon: Max Headroom, the Star Trek Holodeck, the first CAVE setups in colleges, etc. Since I was interested in Sci-Fi, as well as in illusions and art and spaces, it all made perfect sense. Then in the 90’s I was in college when the computer was introduced in architecture and the visual arts as a tool for creating things, followed by the Internet and its own types of digital environments. So to catch it in my popular culture in my teens and then in college when these things started to actually happen— that really left an impression.

OE: Yes, there’s something quite fascinating about being there right at the moment where the analog is still fully present and the digital is coming into its own, and you’re young enough to still be able to join this revolution but you’re also old enough to know the world without it.

PG: I was fascinated with computers at the time but also so frustrated by them. They were so primitive in retrospect. When you were constructing digital models it was just barely faster than modeling by hand! I was pretty good at drafting at that point so I was starting to realize how similar they are, but because one language hadn’t really developed beyond just a computer version of drafting, I was still able to see them both simultaneously. It took me longer to put the words to it though. For a while I was just talking about digital-analog relationships. Then I realized this other relationship, of the real and the virtual. So the virtual is a construct for seeing, while digital and analog are just different processes that allow you to create the virtual. So virtual and digital are not somehow opposed—one is a strategy and the other is a tactic. To experience and manufacture virtual space, you can use a digital means or you can use analog means. That’s where I started thinking about it. How did you come to realize that the virtual and the digital are separate?

OE: To me the distinction between virtual and digital came from the combination of having studied architecture, then computer science and later getting into digital imaging. I was searching for the essence of virtuality, but the more knowledge I gathered the more I realized there is nothing virtual about all these technologies that I’m learning. It’s not there. It’s not in the computer. Then I finally realized that if I want to find it, I should rather follow the art path, both in practice as well as studying its history. Eventually it came together for me during my doctoral studies in architecture, where I combined my gathered experience in these various fields in a research form. Since then I have continued to develop and expand what I call “The Virtual Space Theory”. (see: Or Ettlinger, The Architecture of Virtual Space, Faculty of Architecture of the University of Ljubljana, Ljubljana 2008)

PG: So now when you write or lecture, what have you found are the most contentious or controversial things that people react to? What are the things that you say that maybe in your own head are obvious but there’s a lot of resistance or questioning by people when you actually talk to them?

OE: I found that most people do tend to listen and consider the ideas I am proposing. The few tough reactions I did get, however, typically were from people who deal with topics that use the same terminology although they are still quite different topics than mine, and they are offended that I seem to take the word away from them. So, for example, I had a much older colleague in my faculty who strongly argued, “No, virtual is what you see in your mind!” But this is another important distinction I came across during my research – that what you see in your mind is rather your mental space, where you can create mental simulations. For example, if you are trained to do so, when you look at plans and section drawings, you can construct a three-dimensional image of a building in your mind. But that is not a virtual building – it’s a mental building, which is short for “a mental simulation of a building in your personal mental space.”

PG: It’s a good point. I never made that distinction. You’re absolutely right. To me, the virtual building is the thing on the paper. It’s the coded construction that implies the final thing. You putting it together in your mind is not the virtual image. You’re using a virtual tool to create a mental picture, a mental simulation in your mental space. I would agree with that, but I never actually put it this way. Now it’s starting to make me come back through a lot of my comments and a lot of my statements about where I suggest or imply that virtuality exists. Is it in the media? Is it in the reception of it in your eye? Is it in the mental space? Hmm, it’s definitely not in the mental space. I’ll have to think about that one.

OE: Actually, it goes on even further, because—at least according to my terminology—plans and drawings are not virtual either. They are simulation aids that help you construct the simulation of a particular building in your mind.

PG: OK, so maybe you can define simulation and how it’s different from virtual?

OE: Hmm… I would say that a simulation is something that recreates some of the external characteristics of another thing but not its essence. So in such contexts, to me, the opposite of real is not virtual, but rather simulation. Virtual is not even on the same axis. It’s something else altogether.

PG: So you make a parallel distinction between virtual and simulation?

OE: There are many kinds of simulation. It’s a certain act, or process, which involves a simulator and refers to a simulated, and where each of them can belong to an entirely different environment. Actually, much of your work is all about exploring “what if I simulate X in environment Y?” or “what if I simulate Y in environment X?” and so on. You engage with all these different modes and you’re so familiar with them that you can play with “which aspects do I take and which do I leave behind?” as you describe one in terms of the other.

PG: Yes, it’s a nice way of describing it.

OE: And then one of these modes of simulation involves having a physical object that gives you a visual experience of space that is physically not there. Normally we would just call it ‘a picture’, but it’s a type of simulation, a simulation of space. That particular type of simulation is what I call virtual. And I call it virtual because the space that is not there is not even tied to the physicality of the object you see it through.

PG: Oh… I see.

OE: As long as the simulation is tied to the physicality of the simulator then you don’t even need the word virtual. You can just say that it’s pictorial. In the classic literature of art theory, it’s just talked about as ‘pictorial space’ or ‘illusion space’. Physical objects that when you look at them you might not even notice the physical object. You see a simulation of space as if through it.

PG: Right, the Renaissance painting.

OE: The Renaissance painting, or the modern photograph, and now also digital imaging.

PG: Sure, yes.

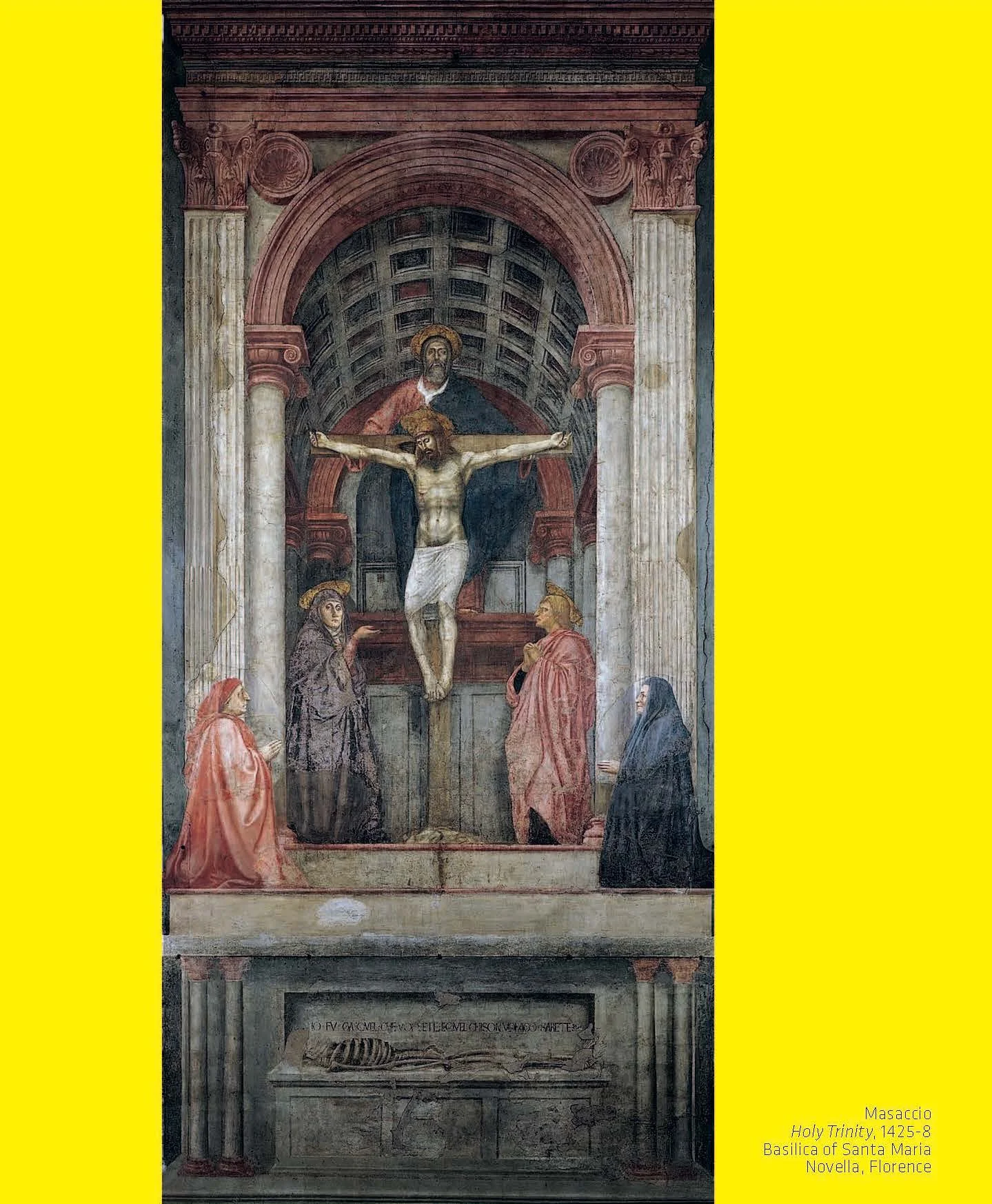

OE: When you have a painting, say, Masaccio’s Trinity, it’s huge, and it’s painted on the wall of that church and it creates the ‘illusion space’ or ‘pictorial space’ that looks like an architectural vault behind it. But nowadays you can open a book or go online and see the exact same space. Technology has made it all so interchangeable that seeing this ‘pictorial space’ doesn’t even require a particular picture object. They are no longer uniquely tied to each other. So to me, the term ‘pictorial’ just doesn’t apply anymore because it describes only the particular space behind a particular physical picture. But if our interest is in the space of Masaccio’s vault—the same single space which can be seen through all of the multiple copies of this painting—then you can no longer call it pictorial. And yet the space is there. You can see it, so this is what I call…

PG: So that’s virtual.

OE: That’s virtual.

PG: It sounds like it’s an argument on the liberation of the content from its context, in a way, so in the Masaccio example, you are not restricted to seeing it as the original object anymore. You can liberate the content of that object from the object itself, and see it in other forms.

OE: You’re right, and to be more specific, you might say that it’s a liberation of the content of the image – or what I call the ‘virtual place’—from the physicality of the picture object.

PG: So part of the argument is wrapped up in the mechanical reproduction line of inquiry.

OE: True, the age of mechanical reproduction was one major step, but then it went on. Now we’re in what I would call ‘the age of digital abstraction’, in the sense that the physicality of the picture objects has been reduced to photons on versatile screens and to electrical signals in miniaturized chips.

PG: Right, it takes a bit of paint on a wall, which has to be converted into a pixel or some other analog and allow it to become reproduced in other ways, but it ends up in your book, after it went through a series of abstractions from paint on the wall to pixels on a screen to droplets of ink on a piece of paper…

OE: Yes, yet when you look through each of them you still see the exact same place. These are two copies of the same painting, but not copies of the place. They are like two separate windows, but the place you see through them is the same one.

PG: Right, OK. But if I’m looking at Bruegel’s Tower of Babel, at one mental level I am to understand that this is the space of this building, yet on another level I can understand it as a reproduction, a different medium than the original painting. So the virtuality for you is the process by which a lot of this confusion or multilayered action occurs? Or is the image itself virtual?

OE: What you see through the image is virtual. The image is physical. The tower is virtual.

PG: Got it. The idea that the tower is the tower, not dots of ink on the page or pixels on the screen that optically combine to make this thing, but rather, I look at the tower and the tower is virtual.

OE: And the tower is the same if you stood in the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna in front of the original physical object of Bruegel’s painting. It’s the same tower in both cases. It exists in a certain space that is the same space. So the nature of that space, to me, is what virtual is.

PG: It’s definitely a different definition for me, but what really fascinates me about your definition is that it provides a completely different take on the whole topic of image reproduction. Usually the arguments about reproduction tend to have a pessimistic tone or they are nostalgic for a time when originals meant something. It suggests that we are all wrapped up in the inability to tell truth from fiction because now everything is a fiction, everything is a copy, and there’s no original, and so on. But your definition actually seems to liberate that argument and turn it into something supremely magical and positive because the ability to reproduce Bruegel’s tower has enabled us to almost feel the tower as more ‘tower-like’ than even the original painting could! Because up until a decade or so ago, for almost 450 years since it was made, that painting has pretty much existed as a picture object, and now it can finally exist as something that actually seems, in a way, more real.

OE: We’re closing the circle now… Its virtuality is now the very thing that makes it real.

PG: Right, because it’s liberated from the mediated understanding of it. It’s actually a very lovely circle because I tend to believe that a lot of our progress does not makes things worse, but rather bends towards our general enrichment and expanding of our understanding of ourselves. So in the case of image reproduction, the way you’re talking about it makes it seem like the logical conclusion would be for the proliferation of reproduction rather than the limitation of it.

OE: It makes it irrelevant.

PG: What? Originals?

OE: No, originals are still interesting, but it makes irrelevant the whole apparent conflict between originals and copies, because the copy is not all that important. It’s what you see through it that is important, and that has always been one.

PG: That’s actually a nice argument. So, actually, this brings up something I’ve been wondering about for a long time now: what is the remaining value of going to the museum to see an original? I’m not talking about site-specific installations or works of contemporary art that require personal experience, but going to see an original painting in a museum.

OE: I would have to agree, although my heart still says “No! But the original is important,” so in a way I’m contradicting myself, but the question is what is its importance. It does have an importance but a different one than we would otherwise think.

PG: Right. I don’t need to see the painting to see the image, but I may want to see the painting for looking at brushstrokes or technique, for surface treatment, or for certain art historical significance. That would be a reason.

OE: Yes, and several more along the same lines. But the most important one, I think, is the intensity of the experience of the virtual place you can see through it. The original, in many cases, still provides the best and most engaging view of it. What many works of art—as well as image technology developments—have historically been after is the most immersive experience possible. But sometimes such a peak experience is simply achieved by standing in front of an engaging, well-made, original painting.

PG: Yes, I agree with that. So I think that one of the differences between how you and I use the word virtual is that you necessarily rely on it for a very specific condition that doesn’t have another term—which I think is very legitimate and pretty fascinating and I’m going to hold on to that for a little while and think about it—whereas for me it’s actually more the opposite direction: It’s a way to umbrella a lot of different types of terms that people use interchangeably which are sometimes confusing, a paradigm of the way which humans understand the world.

One of the things that got me into the virtual in the first place was an interest with phenomenology and the wish to understand what reality is. But I don’t have the philosophical training to follow the history of it and put together a new tome about it, so instead, my tools are simulations, renderings, and my ability to draw, to capture something in life. Maybe my studying of the virtual is actually a way to eliminate everything that isn’t real and then what’s left would be a description of what reality is.

OE: That’s a serious motivation for pursuing your projects! It also gives a much deeper context for understanding them.

PG: At the base of it all is the question “why do we seem so interested in making images of our world?” It’s right there in front of us, so why?

OE: Not only that, but why is it that for so many centuries, people seem to take so much pleasure in exploring the limits of our perception, fooling it, playing with it?

PG: I don’t know. I wish I knew. But that question includes a few parallel questions: First, why are people today still fascinated with the techniques of a long time ago? If you show a simple mirror illusion or you show some old technique, people still think it’s amazing. Second, why were people that amazed about it back then? And if they were, was their amazement similar to ours now, and did they similarly think it’s like science at play? And third, does computation enhance or detract from such amazement? Despite all the latest digital techniques, I still find that the simplest illusion is the best one, that something very physical and simple can be so remarkable.

I think we are all pretty much equally fascinated but we are not fooled. We are actively aware of our interest and our amazement while we are being amazed. There’s this story about the Lumiere brothers and the film of the oncoming train where the audience, who had never seen a film before, ran out of the screening hall screaming as the train was approaching. But I don’t believe it! I don’t think anyone is ever confused by any media that is highly realistic. There’s the wonder, the attraction and the amazement, but it’s the confusion that I don’t buy.

OE: That’s a very good distinction. I never thought of it in this way...

PG: It’s wrapped up in a lot of different things, but this idea that we are aware of our amazement is really fascinating, which is why your description of the virtual is intriguing because it’s actually the opposite—you’re making something amazing out of what we’ve all taken as something really boring. We look at an image as “oh, it’s just a reproduction,” it’s actually value-less, or of very low value or cost, and yet it now suddenly has value because it’s contributing to this much more rich experience of the space itself, not the picture object.

OE: The virtual place.

PG: So the virtual place now emerges because we have these pretty much valueless or cheap, or denigrated aspects of contemporary culture, “oh, it’s just a bunch of copies”, and yet it actually seems to resonate. I think what we’re circling around a lot is that weird aspect of ‘the thing itself’. It’s very much so in architecture, because it’s always conjecture and proposition and never the thing itself. As architects, we don’t actually get to build much, and even when we do, what we ourselves produce is not the building but drawings of it. So, for me, for a while I got really caught up in drawing because that I could control and make these huge or very intricate pencil drawings and explain them as a building of some kind, though what I had were only drawings. But even now, for example, take my project with the clamp-ons that you put onto chrome pipes to create a reflection of a ‘memento mori’ skull. What I make is not the thing itself either, because the thing that I make is not the skulls that emerge as an image but the clamp- ons! They cannot be divorced from the thing itself, but really the point of it is to look at the reflection.

OE: That’s a recurring theme in most of your projects. I actually made a little list of projects that I was looking at on your website and tried to analyze them from my perspective, to figure out what you are trying to do there…

PG: Tell me. I’d love to know.

OE: It seems like your interest is in simulations and in simulations of simulations, and then hacking the whole system behind them and bending it to perform an entirely different task than they were originally designed to do. By hacking I don’t mean the anarchist computer whiz who is out to mess up with the establishment… but rather the mindset of figuring out how something works and then readapt it to do something else. And in your case, you apply that to older tools and mediums. So you explore forgotten technologies like these centuries-old plotters or ‘drawing machines’…

PG: And set them up to produce drawings of drawing machines.

OE: Exactly, that’s a type of ironic twist that is very much a contemporary way of thinking, like a hacker, but you apply it to old tech. And then there are all these simulations, a physical object that simulates a virtual object, and a virtual that simulates another virtual that simulates a physical, and back and forth – your interest is in these transfers from one to another. It’s not so much about the content of what is transferred but about exploring these passages from one environment to another. For example, in Incident Angles you take classical paintings and make photographs of them from an angle from which they no longer function as paintings at all – you hacked these ‘spatial simulators’ into becoming inert space-less objects.

PG: It’s actually very funny, now that you say that. In relation to some of the language used before, it is a project that quite literally takes the picture object as the subject, like the object becomes the subject, not the conceptual construct in which that object operates.

OE: Right. Then a totally different project but with the same mindset is the iPhone Panorama. There you have a device that is carefully built—this App with all the hardware on which it operates—to take a physical place and create simulations of it as a virtual place, but then you intentionally misuse this simulator in a calculated way that would make it produce a completely different virtual place than it was intended to. Perhaps one that breaks the rules of physics, or of logic, and yet it has its own strange consistency because you do use the simulator.

PG: I do like hacking. I like the term. Transfer and passage are good terms too. So what else do you have on your list?

OE: Your Vantage Tees are also hacking tools. In one of them you have a T-shirt with an image of the ‘memento mori’ skull made of dots, where from up close you just see dots, but from a distance you recognize it for what it is. But an even better one, which took me longer to realize, is the one with a distorted image turned into a personal T-shirt which only the person wearing can see correctly – a sort of personal anamorphosis. But the real hack here, to me, is that you take the classical idea of the ‘punto stabile’—the unique point in the room where an illusionistic mural appears visually correct—and you turn it into a mobile point. You carry the ‘punto stabile’ with you everywhere! That’s some big-time hacking right there.

PG: That’s actually a nice way of saying it. I may be a little limited with my digital expertise and I can’t just code my way through, but technologically I feel very broad because I borrow from old technologies. I’m intrigued by simple mechanical linkages that simulate vision. That’s incredible to me. Actually I have as much fascination in our web culture, selfies and portable technology as I do with ancient stuff. It’s just that my hacking skills are more limited in contemporary technology, but expansive when you consider the history of technology.

OE: It’s ‘old media hacking’ in a way. It sounds like your sense of personal exploration and satisfaction can be found not only by going forward to something that has not been developed yet, but also by going backwards to revive something that has become obsolete.

PG: That’s a good point. There’s something exhausting in keeping up with the new phone, the new technology, the new software. I definitely find a certain kind of peace and calm in looking at these old books and knowing that that information has been there for 250 years, and I am now learning it for the first time and sharing it with others. That said though, without the Internet I wouldn’t have 95% of the research that I have. Like your book, I would have probably come across your website sooner or later, but I’m glad I have it as a book.

PostScriptUM #19

Series edited by Janez Janša

Publisher: Aksioma – Institute for Contemporary Art, Ljubljana www.aksioma.org | aksioma@aksioma.org

Represented by: Marcela Okretič

Proofreading: Phillip Jan Nagel

Design: Luka Umek

Layout: Sonja Grdina

(c) Aksioma | Text and image copyrights by authors | Ljubljana 2015

Printed and distributed by: Lulu.com | www.lulu.com

In the framework of Masters & Servers | www.mastersandservers.org

Published on the occasion of the exhibition:

Pablo Garcia

Adventures in Virtuality

www.aksioma.org/adventures.in.virtuality

Aksioma | Project Space Komenskega 18, Ljubljana, Slovenia 2–18 April 2014

The project was realized in partnership with FH Joanneum, Graz and with the support of the Ministry of Culture of the Republic of Slovenia and the Municipality of Ljubljana.