3D Before Now

This exhibit was curated and designed as part of ART&&CODE 3D 2011, held at the STUDIO for Creative Inquiry at Carnegie Mellon. The exhibit contained original 3D devices from the last 125 years, displayed to encourage audience first-hand experience. From the exhibit literature:

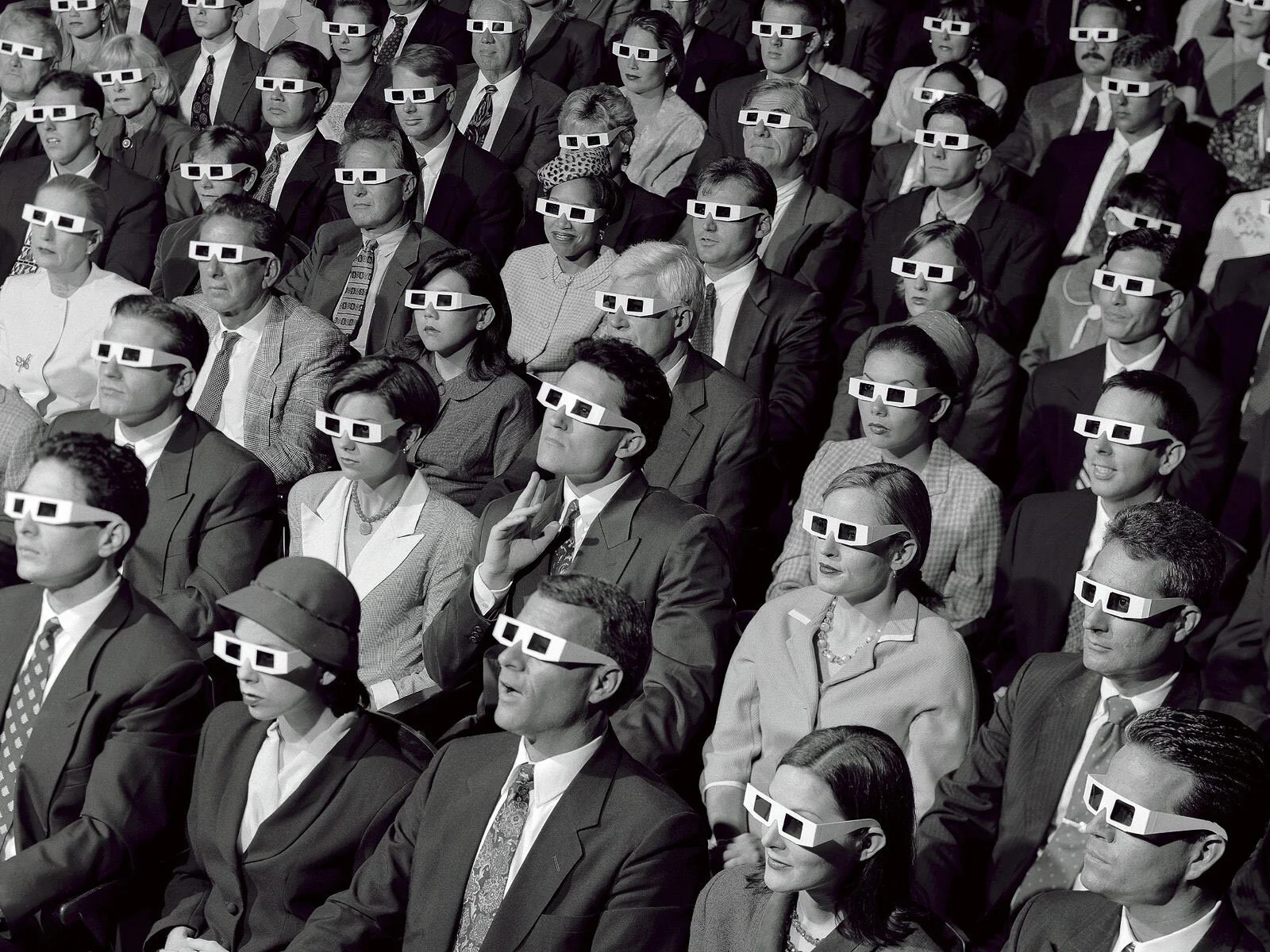

21st century 3D technology is the third great craze over stereoscopy. The late 19th century introduced the stereoview to the masses, only to see its decline in the age of cinema. Hollywood resurrected the technology in the mid twentieth century for monster movies, launching a popular fad for plastic red and blue glasses. As Avatar and the Kinect mark the newest iteration of stereoscopic entertainment, this exhibit looks at centuries of popular three-dimension images and devices—some part of mass entertainment, some as niche applications of stereoscopic techniques.

Something as seemingly simple as binocular vision did not have an author until Sir Charles Wheatstone. In 1838, he described stereopsis as the complex coordination of two slightly different vantage points from each eye to create the illusion of depth. What is probably more remarkable was that he was able to synthesize this process with lenses, mirrors, and a pair of images made from the same vantage point discrepancy. Stereoscopy, as a science, was born. To become entertainment, Wheatstone’s discovery was fortunate to be made precisely at the same time as the invention of another great optical process: photography. Once photography came of age, and amateurs became fluent in making images, 3D images—stereoviews—invaded the homes and parlours of a populace hungry for visual entertainment.

Stereoscopy—as a form of popular entertainment—enthralls the masses because of its magical and wondrous illusion. In that vein, it fits neatly alongside other Victorian devices of illusion and wonder. The high watermark for stereoscopy in the 19th century coincides with magic lantern projections and phantasmagoria, popular photography, and cinema’s ancestors like the kinetoscope and mutoscope. Opticality was all the rage, and it gave birth to the Modern paradigm of vision we now refer to as mass media. But while the other optical toys of the Victorian age continuously evolved into forms we now today, 3D images would occasionally appear to enthrall and delight only to be dismissed or superseded and then rise again. Magic lanterns and flip-book images became cinema, photography evolved into color and digital versions of its former self. Stereoscopy comes and goes with generational frequency, as though the wonder wears off until a new, unaware population grows up and discovers it all over again.

It’s very much de rigueur to weigh in on the successes and shortcomings of the seeming avalanche of 3D movies this past decade. Everyday someone promotes a 3D experience as revolutionary as another denounces it all as a fad. It’s quite possible all the stereoscopy conversation going on at this Art&&Code workshop will be moot in ten years as 3D hibernates until the next time around. But perhaps this time it sticks because it is not only a form of mass entertainment, and the wonder comes not from the 3D illusion, but how easy it is to participate in the stereoscopic sandbox. And—as those who applied 3D to other fields beyond entertainment in the lull periods—perhaps the future of 3D is not merely watching movies with fancy glasses, but new potential for the next age of digitally-inspired vision.

Exhibit designed and curated by Pablo Garcia from items in his collection.

Installation team: Madeline Gannon, Chris Williams, Spike Wolff